Guarantee

A legal promise made by a third party (guarantor) to repay a borrower’s liabilities (typically funded debt obligations)

What is a Guarantee?

A guarantee is a legally binding agreement signed by a guarantor, on behalf of a borrower. It guarantees that, should the borrower trigger an event of default that cannot be remedied, the guarantor will make the lender whole on its credit exposure.

A guarantee can be signed by any number of third parties, although the guarantor often has some connection to the borrower. Consider a corporation that is the legal borrower of commercial credit, but the debt may be guaranteed by the owner (or owners) of the business. In personal lending, a student loan may be guaranteed by the parent(s) of the borrower, since the student has little-to-no income at the time of underwriting.

From the lender’s perspective, a guarantee is considered a form of indirect security. In general, a guarantee won’t make a bad deal a good one, but strong indirect security can make a good deal a much more attractive place to deploy capital.

In many jurisdictions, a guarantee that is financial in nature is referred to as a guaranty.

Key Highlights

- A loan guarantee is a legally binding agreement that serves as indirect security for a creditor.

- A guarantor can be an individual, a related corporation, or even a non-arm’s-length entity like a development bank.

- The credit exposure covered by a guarantee may be limited or unlimited.

- A guarantee generally does not make a bad deal a good one, but it can dramatically improve the risk profile of an already attractive deal.

Security & Loan Loss

Lending is a relatively low margin business, so creditors go to great lengths to mitigate against loan loss.

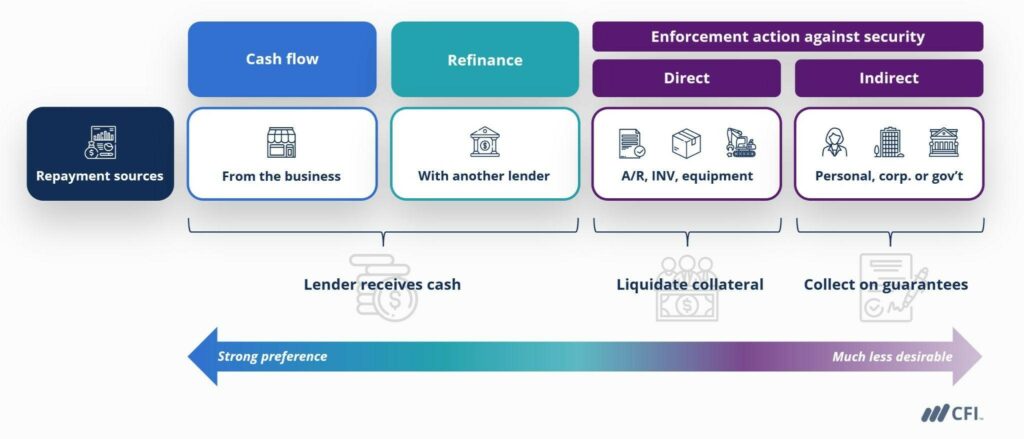

If a borrower triggers an event of financial default, the preferred course of action is to fix the default or have the exposure refinanced with another creditor. Of course, that doesn’t always work, so lenders often structure loans using a variety of direct and indirect forms of security to help prevent loan loss.

Direct Security

Is when credit is backstopped by a specific, underlying physical asset that serves as collateral. Examples include equipment (for a commercial loan) or a home (for a residential mortgage loan).

If a loan in default cannot be fixed or refinanced, the lender’s next step is to take enforcement action against this direct security; this could include liquidating the equipment or foreclosing on the home.

Some jurisdictions restrict secured lenders to either “seize or sue” for the amount outstanding. This means if the asset is repossessed, the lender may not also sue to get a judgment for any remaining amounts owed under the conditional sales contract. In other “seize and sue” jurisdictions, however, the lender may do both.

Indirect Security

Indirect security is sometimes called external or alternate “recourse” (because the lender still has some other recourse over their funds).

Imagine a scenario where, after liquidating direct security, there is still a residual amount of credit outstanding; this is where indirect security comes in, and guarantees are the most popular form of indirect security for most financial institutions.

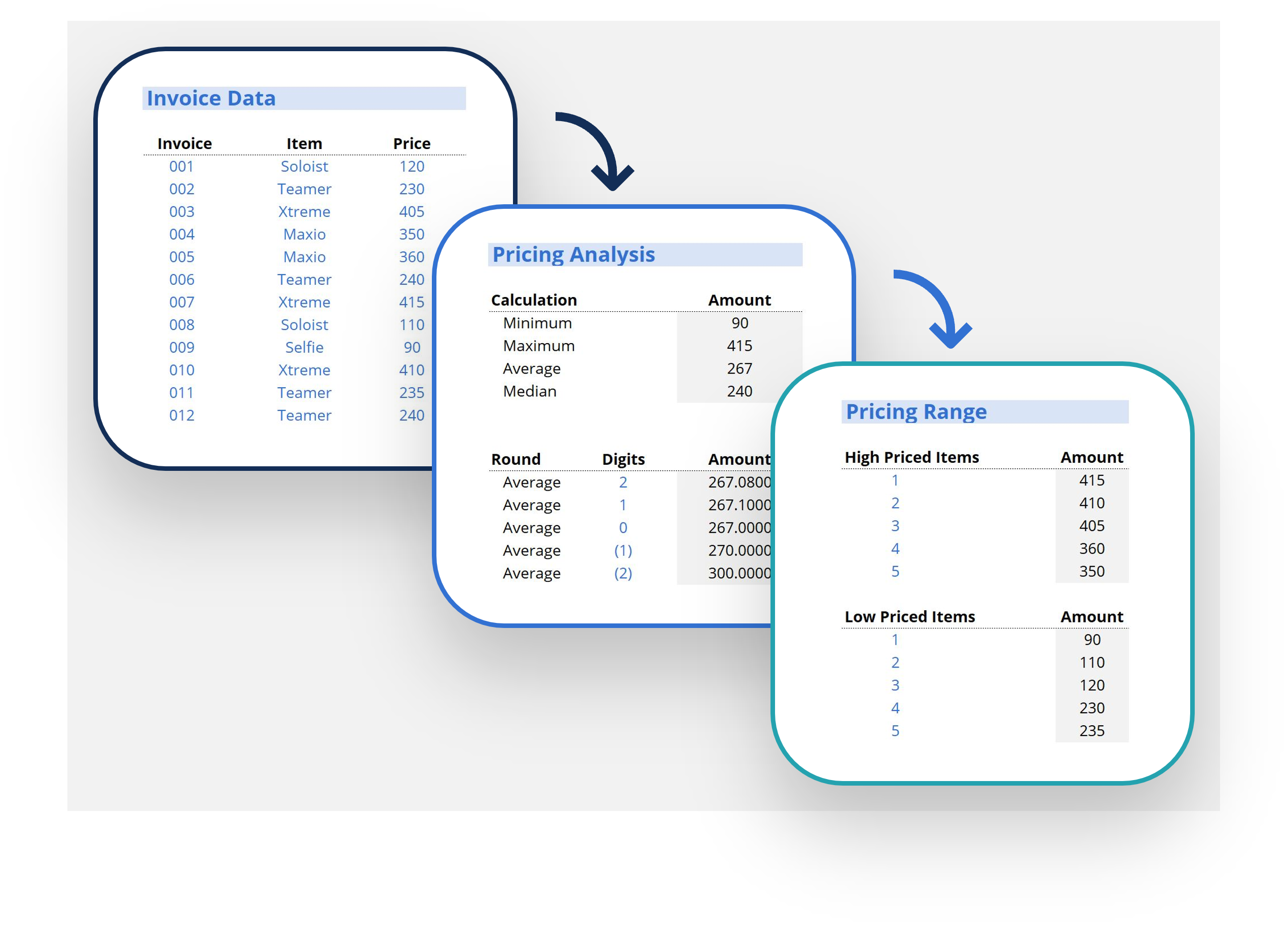

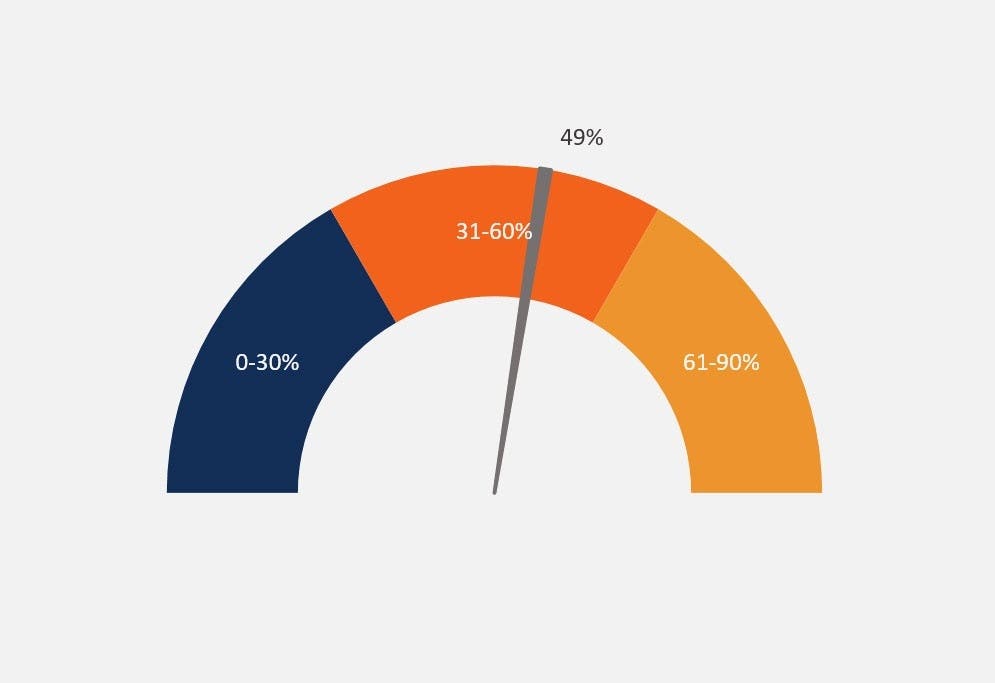

You’ll note in this diagram that the order of preference in terms of loan repayment/recovery is cash flow, followed by refinancing, then enforcement action against direct and indirect security.

What Makes a Strong Guarantee?

Since guarantees are legally binding, the strength of the contract itself is important. Many financial institutions use standard language in their guarantees, language that has been vetted by legal counsel to reduce this risk.

The next consideration is the financial strength of the guarantor (or guarantors). A guarantor could be:

- An individual, including a business owner or a family member of the borrower.

- A corporation, including a commonly-owned holding company or operating business that has sufficient economic value to justify the agreement.

- An unrelated organization, including government agencies and development banks, that exists in some jurisdictions to support entrepreneurs by guaranteeing credit through different insurance instruments.

A lender must be vigilant in understanding and adjusting a guarantor’s net worth when evaluating how suitable they are as a guarantor.

Corporate vs. Personal Guarantees

When a corporation serves as a guarantor, many of the same principles apply. The corporation must either possess surplus (liquid) assets or consistently generate surplus operating cash flow (or both) for the arrangement to make sense.

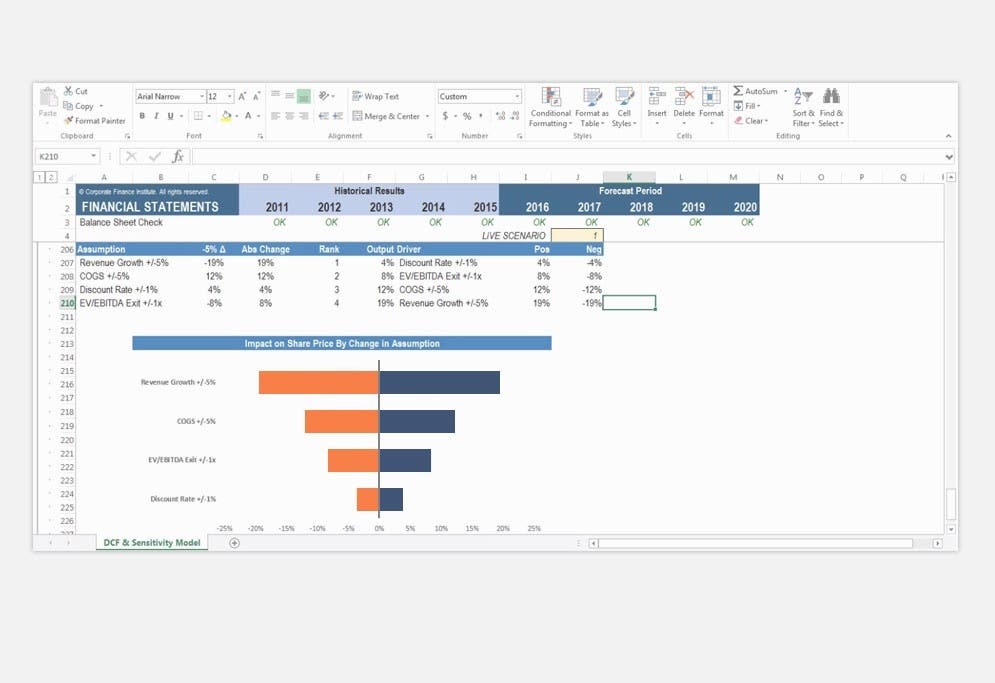

But corporate guarantees are inherently more complicated. Instead of the lender having to understand and adjust an individual’s net worth, they must analyze and quantify the guarantor corporation’s financial well-being, which includes a much more robust due diligence process.

Additionally, the lender must also register appropriate security charges against the guarantor corporation in order to ensure legal enforceability.

Limited vs. Unlimited Guarantees

Guarantees generally come in two forms – limited and unlimited.

Limited Guarantees

As the name suggests, limited guarantees put a cap on the amount that the guarantor can legally be obliged to pay.

An example is if a business borrows $1MM to expand and the owner agrees to a limited guarantee of $200,000. In the event of a worst-case scenario, that guarantor could not be asked to pay back more than $200,000, regardless of what is owed.

Some jurisdictions set limits and requirements for guarantees to be legally valid.

Unlimited Guarantees

This name is somewhat misleading, as it implies that the guarantor could be on the hook for an “unlimited” amount of money.

That’s not actually the case, as a lender cannot legally collect more from a guarantor than is actually owed to the financial institution. As a result, the total credit exposure serves as an implied upper limit on the guarantee amount.

One exception is accrued interest. A lengthy liquidation process may result in considerable accrued interest owing, which is included under the terms of most unlimited guarantees.

Multiple Guarantors

Commercial lenders frequently come across scenarios where a business has multiple owners; depending on the credit structure and risk profile, this may require multiple guarantors.

Let’s use an example to illustrate:

A business is owned 50/50 by two founders. The business borrows $1MM from its commercial bank, and the proposal requires a 50% covering guarantee (so a total of $500,000 in limited guarantees).

The two owners will be “joint guarantors,” as their obligations are spread equally in the same way as their ownership. They can negotiate separate guarantees independently or they can sign one guarantee “jointly and severally.”

Independent Guarantees

In this case, each owner could sign an individual personal guarantee for their own respective $250,000 (determined by their 50% owners multiplied by a 50% covering guarantee required by the lender). This is known as a “several” guarantee.

In the event that enforcement action was taken against the company’s guarantors, each would be responsible for up to $250,000; if party A paid but party B did not, the lender can’t sue party A for party B’s share.

Some guarantees are signed as a percentage of a capped amount. So each individual signs a separate 50% guarantee for $500,000. This is different than the above, as their obligation will never exceed 50%, rather than $250,000.

Joint and Several Guarantees

In this case, both owners would sign the same $500,000 limited guarantee. In the event of enforcement action, BOTH party A and party B are jointly responsible for the full exposure. So if B didn’t pay anything, party A could be individually compelled to pay the entire amount. Party A may make an individual claim against party B later after settling the debt.

In general, lenders prefer joint and several guarantees, while business owners usually prefer to avoid them where possible. This is because when lenders seek repayment, claims against some guarantor may be easier to resolve than others, perhaps due to costs or accessible net worth.

When business owners are required to serve as joint and several guarantors they may choose to negotiate side agreements committing to one another that the other partner(s) will not be left legally liable for the full repayment obligation of the borrowing entity.

Independent Legal Advice (ILA)

In some instances, there may be a requirement that an individual who is not actively involved in the business serve as a joint guarantor; this could include the spouse of an owner or a non-operating shareholder, among others.

Most lenders require that these non-active guarantors retain what’s called independent legal advice from a lawyer of the guarantor’s choosing. This confirms that they understand what’s being asked of them.

Without ILA, it would be easy for a guarantor that is not involved in the business to, after the fact, make a very compelling legal case that they didn’t really understand what they were signing.

Personal Guarantees – the Bottom Line

When it comes to personal guarantees on corporate debt, specifically, commercial lenders rarely want to actually take enforcement action on them.

A really important justification for their inclusion in many transactions is to ensure that the guarantor (in most cases the business owner) remains at the negotiating table if things go severely wrong.

Because corporations are separate legal entities, a guarantee may be the only thing tying the owner(s) to the funded debt obligations of a non-performing business.

Guarantee vs. Bank Guarantee

A guarantee, as outlined here, refers to a guarantor offering alternative recourse (or indirect security) to a lender. A bank guarantee, on the other hand, is when a bank or other financial intermediary provides a guarantee on behalf of its client.

This is a unique field within finance and banking broadly known as trade finance. Trade finance instruments include letters of credit (both financial and performance), letters of guarantee, and bid bonds; all of which exist to help reduce risk in transactions conducted on credit terms between parties that may not be known to one another.

Related Resources

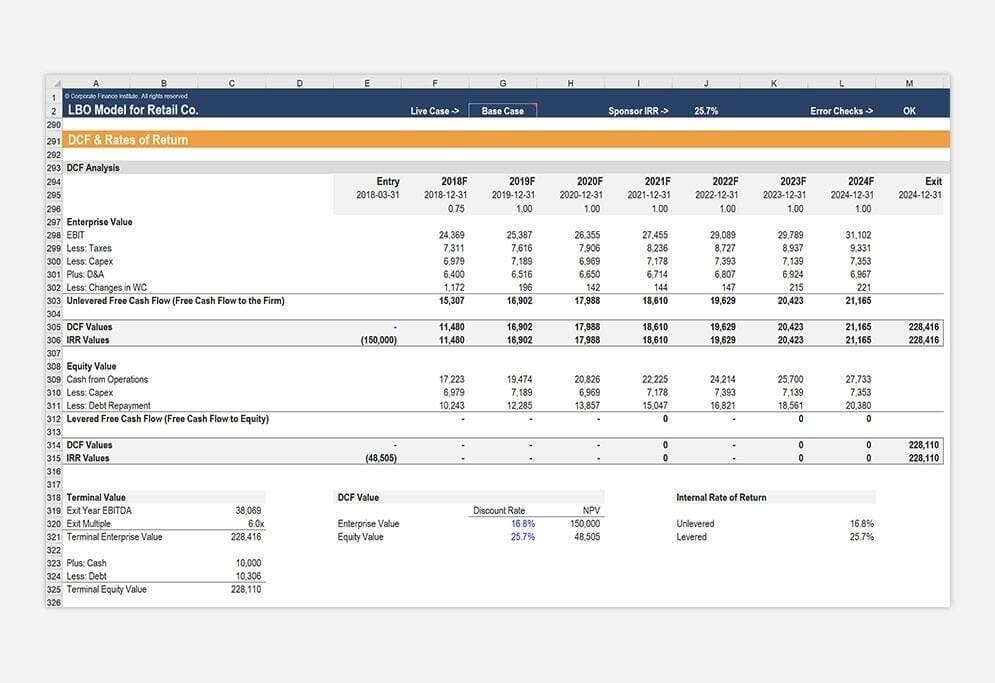

CFI offers the Commercial Banking & Credit Analyst (CBCA)™ certification program for those looking to take their banking careers to the next level. To keep learning and advancing your career, the following resources will be helpful:

Fundamentals of Credit

Learn what credit is, compare important loan characteristics, and cover the qualitative and quantitative techniques used in the analysis and underwriting process.

Create a free account to unlock this Template

Access and download collection of free Templates to help power your productivity and performance.

Already have an account? Log in

Supercharge your skills with Premium Templates

Take your learning and productivity to the next level with our Premium Templates.

Upgrading to a paid membership gives you access to our extensive collection of plug-and-play Templates designed to power your performance—as well as CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs.

Already have a Self-Study or Full-Immersion membership? Log in

Access Exclusive Templates

Gain unlimited access to more than 250 productivity Templates, CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs, hundreds of resources, expert reviews and support, the chance to work with real-world finance and research tools, and more.

Already have a Full-Immersion membership? Log in