- What are Synergies?

- Types of Synergies – Cost Synergies

- Types of Synergies – Revenue Synergies

- Types of Synergies – Financial Synergies

- Modeling Synergies in an M&A Model

- How are Synergies Estimated?

- Hard vs Soft M&A Synergies

- Negative Synergies

- Risks to Synergies

- Some Keys to Successfully Realizing Synergies

What are Synergies? Revenue, Cost, and Financial Synergies Explained

The different sources of synergies

What are Synergies?

Synergies arise in a merger or acquisition (M&A) when the merged value of the two firms is higher than the pre-merger value of both firms simply added together. For example, if firm A has a value of $500 million, firm B has a value of $75 million, but the combined value of the firm is $625 million, we can say there are $50 million in synergies for this merger ($625 – $500 – $75).

Synergies may arise in M&A transactions for several reasons as there are different types of synergies. The two most common “hard” synergies are cost savings and revenue upside.

However, there are other “soft” synergies that may also arise due to a merger. One example is a common corporate culture that will allow the merged firm to be more easily successful.

Below, we discuss a non-exhaustive list of potential types of synergies that a merged company may be able to realize in a transaction.

Key Highlights

- Synergies arise in M&A when the merged value of two firms is higher than the pre-merger value of both firms simply added together. In simple mathematical terms, synergies make 2 + 2 = 5. The increase in value is due to synergies.

- There are several different types of synergies: cost synergies, revenue synergies, and financial synergies.

- Synergies are the source of value creation in M&A; however, it’s possible for companies to experience value-destructive dis-synergies.

Types of Synergies – Cost Synergies

Here is a list of cost-saving synergies that can be achieved when two companies merge:

- Supply Chain Efficiencies: Similar to information technology, if either company has access to better supply chain relationships, there may be cost savings that the merged firm can take advantage of. Additionally, the merged firm likely has greater buying power and can potentially negotiate purchase discounts or other concessions, as well as potentially consolidating suppliers.

- Improved Sales and Marketing: Better distribution, sales, and marketing channels may allow the merged firm to save on costs that were expensed by each individual firm when they were separate.

- Research and Development: Either firm may have had access to research and development efforts that, when applied to the new, consolidated firm, allow for better development or room to cut costs in production without sacrificing quality. For example, one firm may have been developing a cheaper alloy that could be used in the production of an automobile that the other firm produces.

- Lower Salaries and Wages: The merged companies won’t need two CEOs or two CFOs, etc., so there are immediate cost savings by eliminating certain roles. This logic applies down the entire organizational chart.

- Redundant Facilities: Similar to the new, merged firm not needing two CEOs, it will also not need two corporate headquarters. Therefore, one of the headquarters can be closed, consolidating offices. This may also apply to any other redundant facilities, like manufacturing plants that produce similar products.

- Patents and Intellectual Property (IP): If the acquirer used to pay the target firm a fee for access to a patent, a merger may eliminate that expense. This fee effectively becomes an intercompany transaction. Intercompany transactions have no net impact on the merged firm’s financial statements as it’s an expense to the acquirer and revenue to the target.

Types of Synergies – Revenue Synergies

Here is a list of revenue-enhancing synergies that can be achieved when two companies merge:

- Patents: Similar to the cost-saving effect of a patent mentioned above, access to other IP may allow the merged firm to create better and more competitive products that produce higher revenue.

- Complementary products: Both individual firms may have been producing complementary products pre-merger. These products can now be bundled in such a way as to produce higher sales from their customers.

- Complementary geographies and customers: Merging two firms with varying geographies and customers may allow the merged firm to take advantage of the increased geographic and demographic access, thereby producing higher revenue.

Types of Synergies – Financial Synergies

Financial synergies occur when the merged firm is able to better improve its capital structure compared to when the companies were separate. Capital structure changes potentially result in increased benefits in terms of tax savings and debt capacity. If successful, the merged firm can theoretically reduce its cost of capital, thereby resulting in a higher valuation versus the standalone companies.

Below are examples of financial synergies:

- Diversification and Cost of Equity: A merged firm can potentially lower its cost of equity through business diversification. When companies merge, it’s possible the merged firm can increase market share, which can lead to higher revenue and cash flow. In theory, the diversification of the merged firm may result in more stable, predictable cash flows and a lower cost of equity. If possible, the diversification benefit is more likely to come from horizontal mergers versus vertical mergers.

- Increased Debt Capacity: Due to either steadier cash flows or increased firm size, merged firms might be able to borrow more than they otherwise could as standalone, independent companies.

- Tax Benefits: Increased debt capacity could lead to more borrowings. Since interest expense is tax deductible, the merged firm could see a lower tax bill via the use of leverage. Additionally, if a profitable company acquires a company with losses, the merged firm can potentially reduce its tax burden by using the net operating losses (NOLs) of the target company.

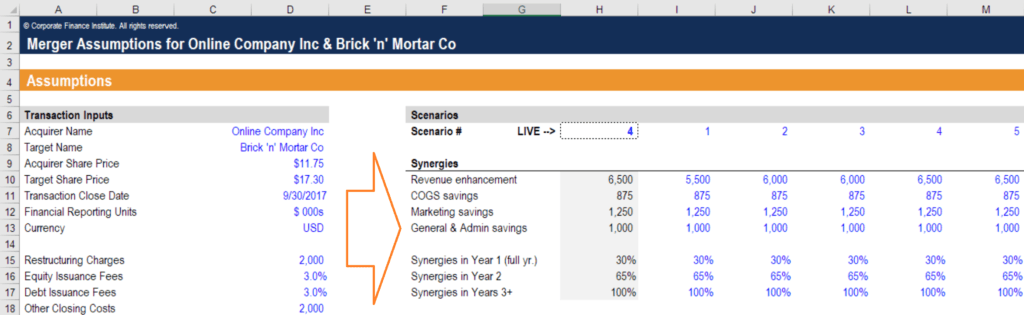

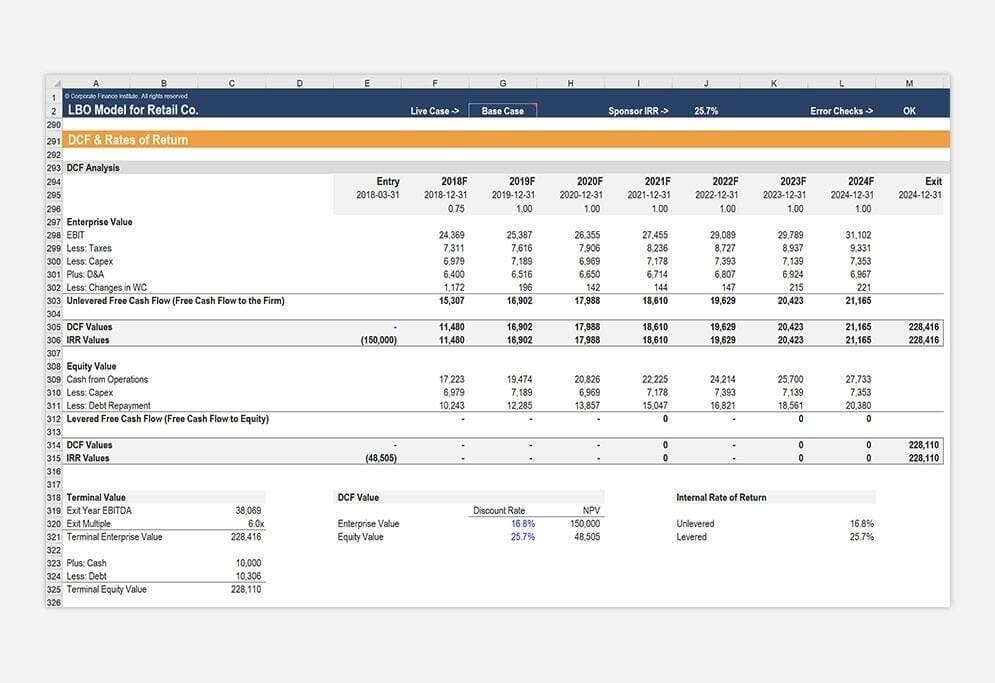

Modeling Synergies in an M&A Model

Below is a screenshot of CFI’s Mergers and Acquisitions Modeling Course. As you can see in the lower right corner of the assumptions section, there are various types of synergies that are incorporated into the model, such as revenue enhancements, COGS savings, marketing savings, and G&A savings.

Additionally, it takes time for the merged firm to actually realize synergies. Notice that in our M&A model, it takes three years for the synergies to reach 100% of their potential impact, as shown in cells H15:H17.

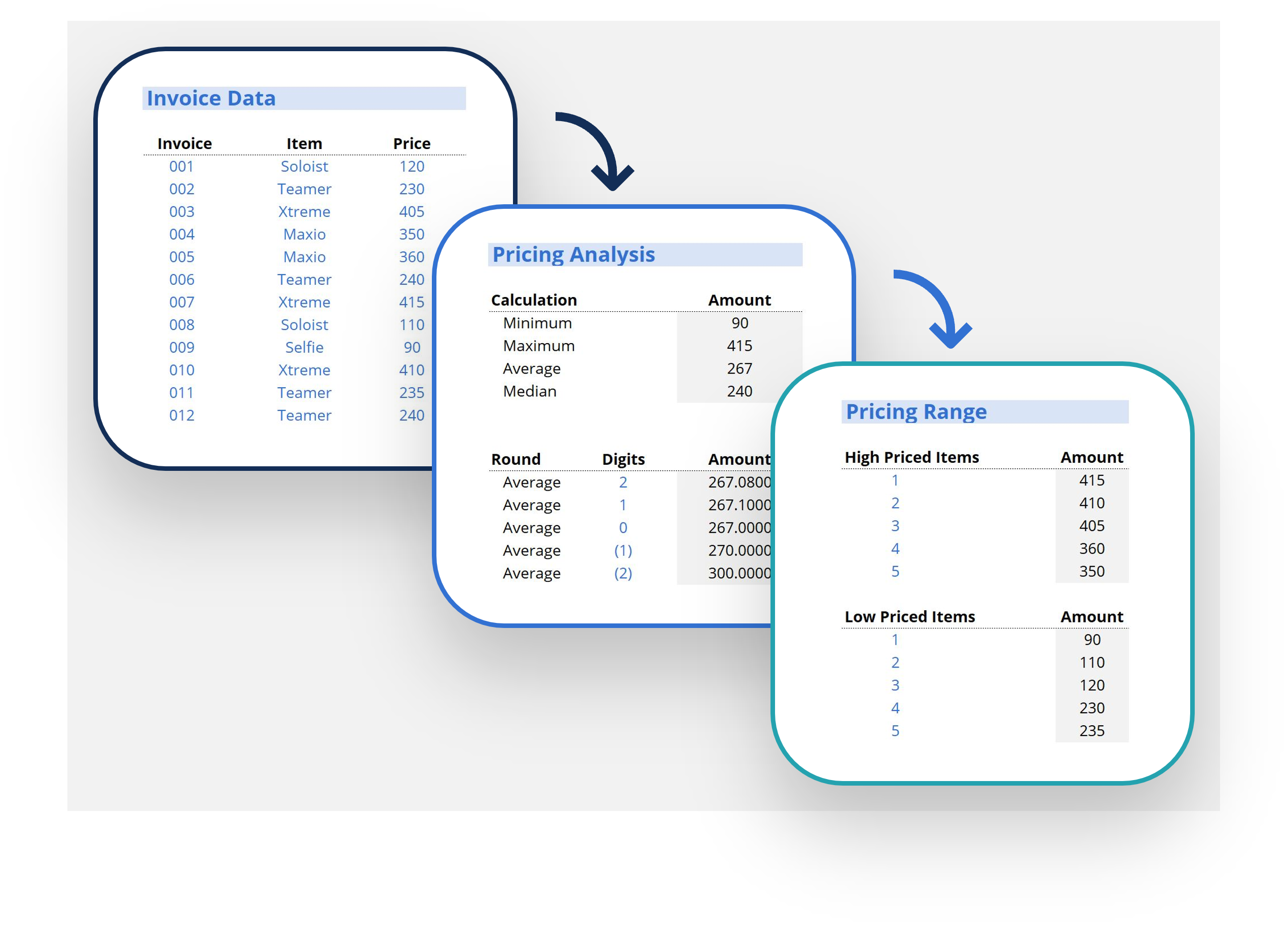

How are Synergies Estimated?

One approach to the way merger synergies are forecasted is by comparing like-transactions. In other words, comparable acquisitions are reviewed as a starting point for potential synergies. As an example, let’s assume a comparable transaction assumed synergies would be five percent of the total enterprise value (EV) of the target. If the transaction we are analyzing is truly comparable, we can assume that synergies should be five percent of the EV as well.

However, it may be initially difficult to quantitatively estimate synergies as the operational intricacies of a combination are not yet known until post-merger. Thus, synergies may be first estimated qualitatively.

Another approach is to look internally at the two companies and perform as much analysis as possible. A bottoms-up analysis should be performed to see how the acquiring firm expects the target firm’s assets and operations to line up and what cost savings can be made. This second approach is more detailed and possibly more accurate; however, it’s very challenging for anyone outside of the deal to accurately perform this analysis themselves.

10 Examples of Ways to Estimate M&A Synergies

- Analyze headcount and identify any redundant staff members that can be eliminated (i.e., the new company doesn’t need two CFOs).

- Look at ways to consolidate vendors and negotiate better terms with them (i.e., purchase goods/services at lower prices).

- Evaluate any head office or rent savings by combining offices.

- Estimate the value saved by sharing resources that aren’t at 100% utilization (i.e., trucks, planes, transportation, factories, etc.).

- Look for opportunities to increase revenue by upselling complementary products or increase prices by eliminating a competitor.

- Reduce professional services fees.

- Operating efficiency improvements from sharing “best practices.”

- Human capital improvements from “top grading” exercises and potential ability to attract superior talent at the merged firm.

- Improve distribution strategy by serving customers with closer locations.

- Geo-arbitrage: Reduce labor costs by hiring in other, lower-cost countries if the target company has operations in those countries.

Hard vs Soft M&A Synergies

There are two main types of synergies: hard and soft. Hard synergies refer to costs savings, while soft synergies refer to revenue increases and financial synergies.

The reason why they are called hard versus soft is because cost savings are usually much easier to actually realize compared to revenue or financial synergies.

Negative Synergies

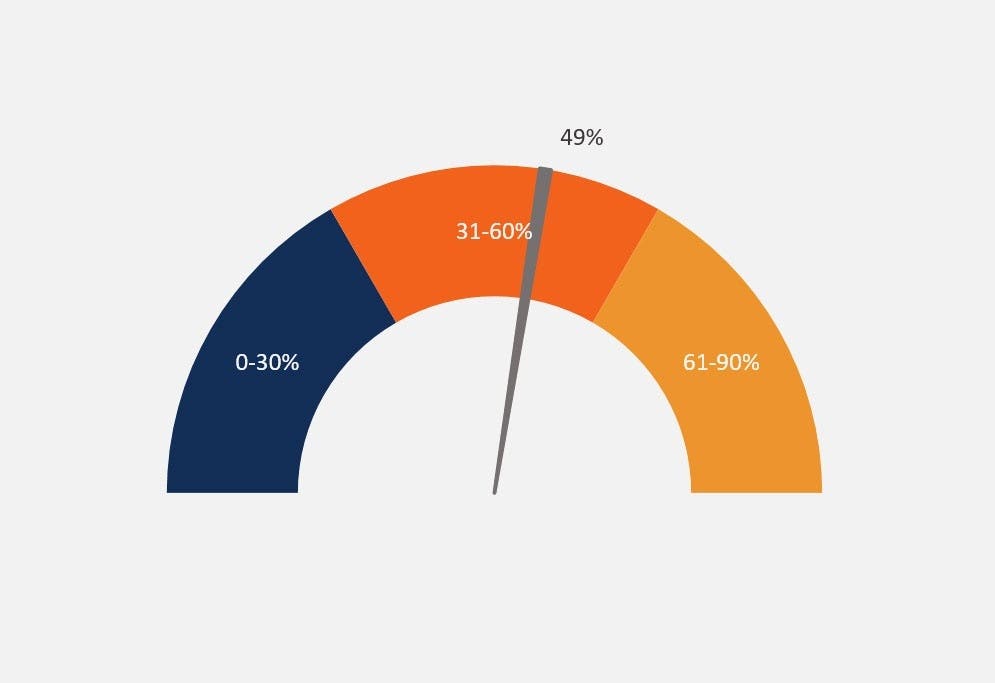

Synergies can also be negative (dis-synergies) if a transaction is poorly executed or integrated. Based on a study by McKinsey, more than 60% of transactions fall short of the synergies they hoped to achieve, and many transactions actually experience negative synergies.

As an example, expected cost savings might actually turn into higher total costs if the two businesses fail to integrate properly.

Alternatively, revenue and marketing synergies may not materialize if the two companies have completely different sales strategies. For example, the Quaker Oats-Snapple deal struggled due to different sales channels (Quaker Oats in large supermarkets, Snapple in small stores or gas stations), in addition to the fact that the products targeted different markets.

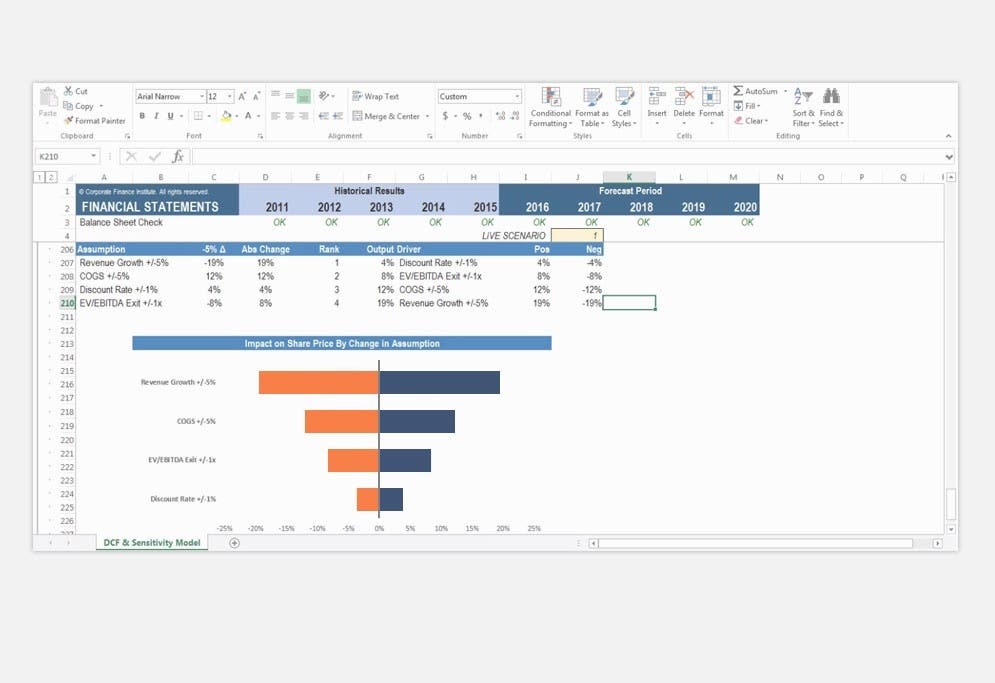

Risks to Synergies

Synergies are not effective immediately after the merger takes place. Typically, these synergies are realized one to three years after the transaction. This period is known as the “phase-in” period, where operational efficiencies, cost savings, and incremental new revenues are slowly absorbed into the newly merged firm.

In fact, in the short-term, costs may actually go up as the integration of the two companies will likely incur various non-recurring expenses, as well as short-term inefficiencies due to a lack of history of working together and culture clashes between companies. If a culture clash is too great, synergies may never be realized.

Some Keys to Successfully Realizing Synergies

- Create an Integration Plan: While lots of thought and analysis goes into analyzing a potential transaction, companies often overlook how to successfully integrate the two companies. Having a thoughtful integration plan is crucial for the combined companies to create value for stakeholders.

- Effective, Transparent Communication: As part of the integration plan, effective and transparent communication is crucial. All employees, regardless of whether they work for the acquirer or target company, must be aware of the integration plan, as well as the benefits of the combined companies. As part of this, management must plan to answer employee questions regarding where the employees will fit into the merged firm.

- Manage Change and Culture: One of the main drivers of negative synergy is when one company’s culture is forced upon the other company. A better approach is to create a new culture that employees from both companies can buy into.

- Continuous Monitoring: To ensure synergy targets are on track, the merged firm should develop a way to measure and track the proposed organizational changes. If any problems arise, this step allows management to proactively adjust the plan as necessary.

Additional M&A Resources

This has been a guide to types of synergies in M&A transactions. CFI is the official provider of the global Financial Modeling & Valuation Analyst (FMVA)™ certification program, designed to help anyone become a world-class financial analyst.

To learn more, see these additional relevant resources below:

Create a free account to unlock this Template

Access and download collection of free Templates to help power your productivity and performance.

Already have an account? Log in

Supercharge your skills with Premium Templates

Take your learning and productivity to the next level with our Premium Templates.

Upgrading to a paid membership gives you access to our extensive collection of plug-and-play Templates designed to power your performance—as well as CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs.

Already have a Self-Study or Full-Immersion membership? Log in

Access Exclusive Templates

Gain unlimited access to more than 250 productivity Templates, CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs, hundreds of resources, expert reviews and support, the chance to work with real-world finance and research tools, and more.

Already have a Full-Immersion membership? Log in