Hard Forks

A split in a cryptocurrency's blockchain that results in a new offshoot cryptocurrency being created.

What is a Hard Fork?

In blockchain technology that underpins cryptocurrencies, a hard fork or (hardfork) refers to a radical change to the protocols of a blockchain network. In simple terms, a hard fork splits a single cryptocurrency into two and can results in the validation of blocks and transactions that were previously invalid, or valid. As such, it requires that all developers upgrade to the latest version of the protocol software.

While hard forks create a permanent chain split with the old version of the blockchain software no longer compatible with the new version, soft forks do not create a new blockchain and so are backwards-compatible.

Key Highlights

- A hard fork is a branching of a cryptocurrency’s blockchain that splits a single cryptocurrency into two.

- This happens when the users of a blockchain cannot come to an agreement on rule changes or upgrades to the blockchain.

- Hard forks are different from soft forks, which doesn’t create a new blockchain.

What is Blockchain?

A blockchain is digital database of transactions that is maintained by a network of computer servers, who can all easily verify and agree on the contents of the database in a way that makes it difficult for anyone to hack or change.

Each one of these users, called a node, stores a copy of the blockchain database (also called a digital ledger). Any new entries to this digital ledger must be first agreed upon before being added to the blockchain. Any blocks that are not agreed upon will not be added to the blockchain and discarded instead.

Once added, new version of the digital ledger is sent to all nodes. As the digital ledger is held by all nodes, it makes it very difficult to tamper with the blockchain and even harder to go back.

The technology was developed to allow a secure way for two parties to deal directly with each other without the need for a third party in between to intermediate. As there isn’t a centralized party, such as a bank or financial institution, that keeps the sole copy of the ledger, you will also hear that blockchains are known as distributed ledgers.

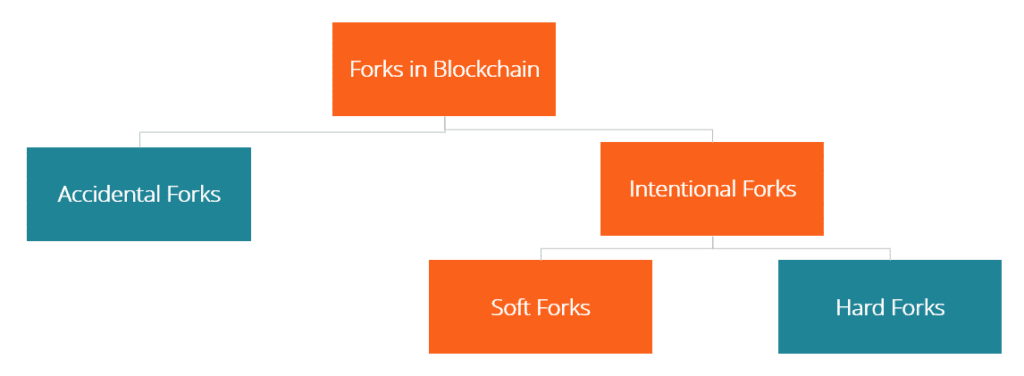

Forks in Blockchain

A fork in a cryptocurrency happens when a majority of the users of a blockchain cannot come to an agreement on an update. Various cryptocurrency networks, including Bitcoin and Ethereum, have experienced hard forks as a result of a lack of consensus for contentious software updates.

Forks can be split up into accidental and intentional forks. Accidental forks happen when two or more blocks are found at the same time, and it is resolved when subsequent blocks are added, and one of the chains end up being longer than the other. The blockchain network then abandons the blocks that are in the shorter chain, referred to as orphaned blocks. The miner that mined the orphaned block loses the mining reward and transaction fees but no transactions would be affected as both blocks would have contained the same transactions.

The second group of blocks, called intentional forks, alter the blockchain rules and includes two different types, including hard forks and soft forks.

Understanding Hard Forks

Hard forks refers to a rule change that comes with wide-ranging implications on the entire protocol of the blockchain network. A fork can be started by the developers of the blockchain or by community members.

Compared to the old rules, the valid blocks produced using the new rules may be viewed as invalid, or invalid blocks will be viewed as valid, which means that all nodes meant to work in accordance with the new rules need to upgrade their software.

A hard fork essentially creates an entirely new currency as it is a permanent divergence from the previous version of the blockchain. One path will follow the new, upgraded blockchain and the other one follows the old path. The users of that particular blockchain can elect to upgrade and follow one path or not upgrade and stay with the other. This is called “backward-incompatible”.

If one group of users (or nodes) uses the old software while the others use the new software, a permanent split can occur. While this sometimes occurs, in other instances, many nodes using the new software may choose to return to the old rules.

However, a more common scenario is that after the new fork is created, those using the old chain realize their version is outdated and less useful than the new one and choose to upgrade to the new one. But it is possible that the two blockchains can run parallel to each other indefinitely.

Not fungible

So does a holder of the original cryptocurrency doubles their money when a crypto hard forks? The answer is not the same as a stock split since in a stock split, each new share is completely interchangeable and substitutable with the existing shares.

But in the case of a hard fork, the old crypto and the new offshoot are NOT interchangable, or fungible. Hence after a hard fork, the original holders don’t lose any of their existing digital coin but instead will get a unit of the new crypto as well.

Both cryptocurrencies maintain their own distributed ledger, so after that point, the two currencies will diverge and started trading at entirely independent valuations relative to each other.

The new cryptocurrency would only be valued by its own supply and demand factors and would not impact the value of the original cryptocurrency. Since the new cryptocurrency doesn’t have any of the value of the old one, the new cryptocurrency would start at a value of zero on until demand outstrips supply and moves the price up, if at all.

Hard Forks vs. Soft Forks

The other type of fork stemming from intention forks is soft forks. Hard and soft forks are similar in that when a blockchain rule is changed, the old version remains in the network while the new one is also present – both creating a split.

With soft forks, a change is made to the software protocol that doesn’t clash with the code and old nodes might accept data that appears invalid to the new nodes without the user noticing. On the other hand, nodes in hard forks will stop processing the blocks following the addition of new rules whereas soft forks allow upgraded nodes to still communicate with the non-upgraded nodes.

Backwards Incompatible versus Compatible

Soft-forks are therefore, backwards-compatible and after the soft fork, still only one blockchain exists as both upgraded and non-upgraded nodes work on the same chain. So it’s more like a software upgrade where you can still read and use older versions of files created by the program.

Because the two versions of the software typically remain compatible in soft forks and not for hard forks, a hard fork creates two blockchains, while a soft fork still remains one blockchain.

Uses of Soft Forks versus Hard Forks

Hard forks are generally reserved for serious upgrades to the network, such as adding new functionality, fixing security issues, changing protocols or in some cases, to reverse hacks to the blockchain. Soft forks are generally used for smaller changes at a programming level that don’t impact the protocol of the blockchain.

You may liken a soft fork to an occasional software upgrade to your computer or smartphone, where a hard fork might be something akin to switching your operating system from Windows to iOS.

Replay Attacks

Since soft forks are less disruptive that a hard fork, soft forks are generally much preferred. In cases where there a fundamental change or a disagreement occurs, a hard fork is potentially messier as the network may become less secure and more vulnerable to attacks. It also creates the risk of double spending in what is called a “Replay Attack”, where a bad actor can intercept a transaction one fork and repeat it on the other chain, making them both valid.

Notable Historical Hard Forks

Both Bitcoin and Ethereum have experienced a few hard forks. Here are two of the most famous ones:

Bitcoin Improvement Proposal 91 (BIP 91)

In the early days of Bitcoin, it had a scalability problem due to the size cap of each block that was put in place by Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonymous founder of Bitcoin. This 1 megabyte cap created some problems, namely the slowing down the speed of the network, limiting the number of transactions on each block and higher transaction fees.

Transaction Malleability

In 2017, however, s part of the Bitcoin Improvement Proposal 91, or BIP 91, Dr. Peter Wuille suggested an idea of a patch meant originally to address a flaw in the Bitcoin code that allowed a type of fraud called “Transaction Malleability”. This is where before a transaction is confirmed, an attacker could in theory change the digital signature of the receiver, generating a different transaction ID – effectively rerouting where the BTC was supposed to go and then telling the sending the coin was never received and getting another BTC.

SegWit

An unintended happy consequence of the amendment (also called SegWit for “Segregated Witness”) was that the main Bitcoin block would allows for almost 4 times more room. Despite all the benefits that the SegWit proposal offered, not everyone was happy when BIP 91 was implemented in on block 477,120 in a soft-fork.

Bitcoin Cash (BCH)

As both sides were unable to agree on a path, on August 1st, 2017, for the first time ever, the BTC blockchain hard-forked into two separate blockchains. The new blockchain was called Bitcoin Cash, or BCH, with a block size cap of 8MB.

The older version of the software was in accordance with the rules valid for Bitcoin, and the other maintained in accordance with the rules that were valid for Bitcoin Cash.

At the instant the hard fork happened, a holder of one Bitcoin automatically became an owner of one Bitcoin Cash as well. By deciding which version of the software to install on their node, the holder decided whether to move onto the new branched Bitcoin Cash or remain with the original Bitcoin, or keep both. In essence, the original Bitcoin had spawned a spin-off currency and BCH was created out of thin air.

The DAO Heist

In 2016, about a year after the Ethereum network was launched by Vitalik Buterin, an organization launched an investor-directed venture capital fund on the Ethereum network. This organization was called “The DAO” and was the first “Decentralized Autonomous Organization”, so it is also known as the Genesis DAO.

Soon after, a hacker or group of hackers exploited loopholes in the smart contract to siphon off 3.6 million of the 12.7 million Ether that was raised, worth about USD70 million by that time, from the Genesis DAO.

The Ethereum community responded by creating a hard fork in order to overwrite the blockchain history and restore the stolen Ether to the original investors, reversing all the transactions done on the entire Ethereum blockchain.

This created a huge amount embarrassment for the fledgling Ethereum, but the hard fork changed the perception that cryptocurrencies were immutable.

Learn More

Thank you for reading CFI’s guide to Hard Forks. To keep learning and developing your knowledge base, please explore the additional relevant resources below:

Cryptocurrency Intermediates: Bitcoin Explained

Bitcoin Explained takes learners on a deeper dive into the world of Bitcoin and explores its history, architecture, and limitations through the lens of an institutional investor.

Cryptocurrency Intermediates: Understanding Ethereum

This course explains one of the most important cryptocurrency networks, Ethereum, and how it is poised to lead the charge for decentralized finance (DeFi).

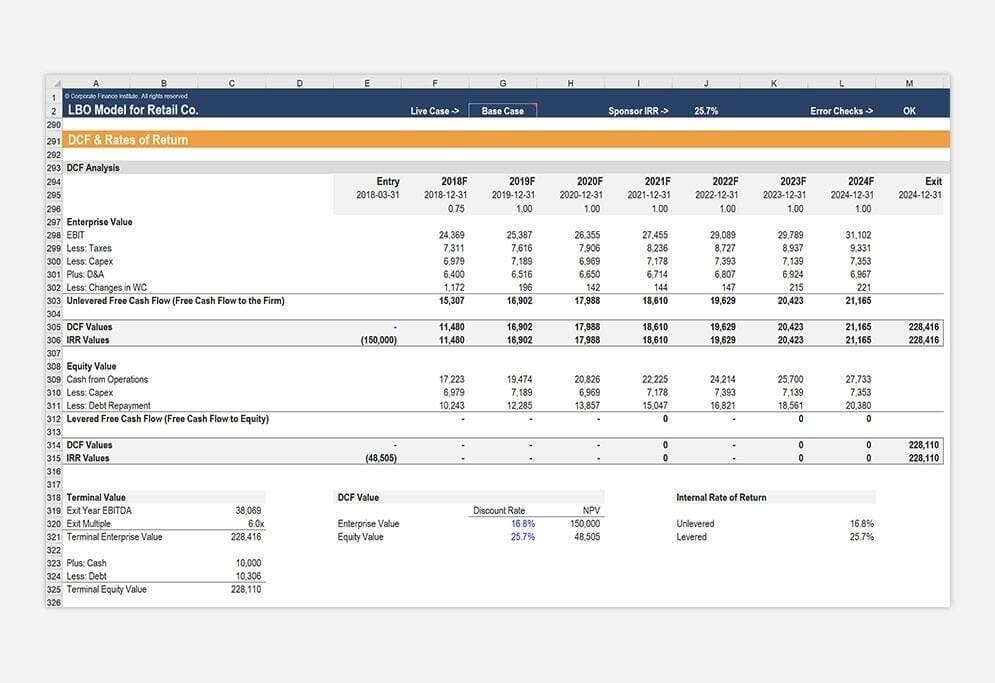

Create a free account to unlock this Template

Access and download collection of free Templates to help power your productivity and performance.

Already have an account? Log in

Supercharge your skills with Premium Templates

Take your learning and productivity to the next level with our Premium Templates.

Upgrading to a paid membership gives you access to our extensive collection of plug-and-play Templates designed to power your performance—as well as CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs.

Already have a Self-Study or Full-Immersion membership? Log in

Access Exclusive Templates

Gain unlimited access to more than 250 productivity Templates, CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs, hundreds of resources, expert reviews and support, the chance to work with real-world finance and research tools, and more.

Already have a Full-Immersion membership? Log in